Daily Brew: October 3, 2025

Welcome to the Friday, Oct. 3, Brew.

By: Briana Ryan

Here’s what’s in store for you as you start your day:

- Voters could decide whether to repeal or keep Missouri's new congressional map in November 2026

- How scorecards and pledges can provide voters with robust information on candidates, by Leslie Graves, Ballotpedia Founder and CEO

- September marked President Donald Trump’s second-lowest month for executive orders in his second term

Voters could decide whether to repeal or keep Missouri's new congressional map in November 2026

The organization People Not Politicians is currently gathering signatures for a veto referendum campaign in Missouri to put the state's redrawn congressional district map on the 2026 ballot, following Secretary of State Denny Hoskins' (R) rejection of the group's initial petitions.

On Sept. 28, Gov. Mike Kehoe (R) approved the redrawn map, which passed as House Bill 1 (HB 1) in a special session of the Missouri General Assembly. In a statement, Kehoe wrote, "We believe this map best represents Missourians, and I appreciate the support and efforts of state legislators, our congressional delegation, and President Trump in getting this map to my desk."

People Not Politicians first filed petitions on Sept. 12 to begin collecting signatures—before Kehoe approved the redrawn map. Richard Von Glahn, a representative for the group, said the map "really represents something that you do see politicians prioritizing themselves over the needs of their constituents. [...] So what's at stake here is people's belief that their democracy belongs and is accountable to them."

On Sept. 26, Hoskins rejected the proposed petitions after Attorney General Catherine Hanaway (R) recommended that he do so. Hanaway wrote in an opinion letter that the Secretary of State could not accept the proposed petition because at the time the governor had not approved the map: "A bill passed by the Missouri House of Representatives and Senate does not become 'a law' until it is either 'approved by the governor' or until the bill is not 'returned by the governor within the time limits prescribed by this section.'"

According to St. Louis Public Radio's Jason Rosenbaum, the organization has filed a lawsuit challenging the rejection of the petitions, arguing that signatures collected before Kehoe signed the redrawn map should count towards the number of valid signatures needed to put the veto referendum on the ballot. The organization submitted another petition on Sept. 29, and the Secretary of State is currently accepting comments on the petition.

In Missouri, proponents of a veto referendum can begin collecting signatures before the Secretary of State issues the ballot language. In 2022, the Missouri Supreme Court ruled 5-2 that a state law prohibiting signature gathering until after the official ballot title of the referendum was certified violated citizens' constitutional right to use the referendum process.

The Court found that the law "dramatically reduce[d] the time available for the circulation of a referendum petition, both in theory and in practice." Campaigns have 90 days after the General Assembly adjourns to submit signatures. The statutes gave the government up to 51 days to prepare the official ballot title, which, according to the Court, could leave campaigns with "39 days under the worst-case scenario" to collect signatures.

To appear on the 2026 ballot, proponents must collect at least 106,384 valid signatures. Missouri bases its signature requirement to put a veto referendum on the ballot on the number of votes cast for governor in the state's most recent gubernatorial election. In six of Missouri's eight congressional districts, proponents must collect signatures equal to 5% of the gubernatorial vote to put veto referendums on the ballot.

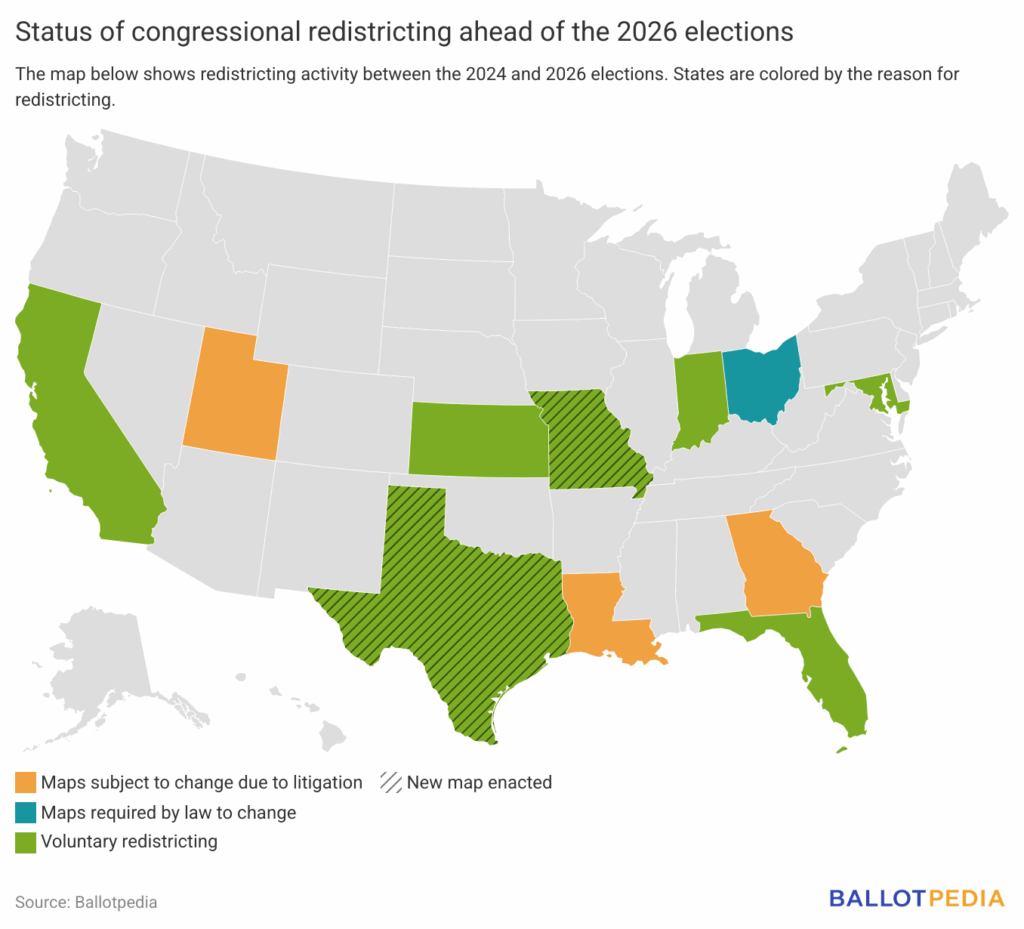

While every state redrew its district lines after the 2020 census, some states are revisiting redistricting ahead of the 2026 elections. Here's where they stand as of Oct. 2:

- Missouri and Texas passed new congressional maps.

- Ohio must redraw its congressional map because of state law.

- Georgia, Louisiana, and Utah have congressional maps that are subject to change due to ongoing litigation.

- Five states were considering a voluntary redraw of their congressional maps, and two states—California and Florida—had taken official action toward doing so.

Missouri voters have decided 25 veto referendums since 1914. Voters repealed all but one of the laws put on the ballot. Click here to read more about the potential 2026 veto referendum in Missouri.

How scorecards and pledges can provide voters with robust information on candidates

Last week, I looked at how endorsements can help provide voters with a more robust and nuanced view of the candidates appearing on their ballots. This week, I want to discuss scorecards and pledges — two additional ways voters can gain a more comprehensive understanding of where candidates stand, and in the case of incumbents, the actions they’ve taken on specific bills or policies.

It’s most common for independent advocacy groups, as well as some media outlets, to use these tools for candidates seeking state and federal offices. Occasionally, pledges and scorecards (also known as voter guides or indexes) may be used in local elections – typically in larger cities, counties, and school districts.

For readers unfamiliar with pledges and scorecards, here’s a brief overview of what they are and the types of information they provide.

📑Scorecards are most useful in identifying how incumbent officeholders have voted on specific legislation that the scorecard’s publisher believes is notable and deserves heightened public awareness. Scorecards can cover single issues, such as climate change, taxation, education, and so on. Some capture a broad spectrum of votes, allowing voters to see whether an incumbent's voting record aligns with their campaign promises or if the incumbent’s policy views have changed over time.

Ballotpedia collects information on scorecards because, while some are either partisan or advocate for a specific policy outcome, they can still be useful to voters seeking a more comprehensive understanding of the candidates on their ballot. (For more information on how we treat scorecards, click here).

✍🏼Pledges serve a similar purpose. When candidates sign pledges, they commit to a course of action or a specific policy goal. These tools are almost always linked to advocacy groups, for whom pledges are a way to demonstrate official support for their agendas.

Like scorecards, pledges are most commonly used for state and federal offices. They may sometimes be used in high-profile local races or for those in bigger cities and counties.

Ballotpedia treats pledges like we treat scorecards. We report as many as we can find and document, and we share that information with voters.

But it’s important for voters to understand that neither scorecards nor pledges are perfect tools for understanding candidates. Advocacy groups choose which votes to score and how to weight them (i.e., making one vote count for a larger portion of an overall score than another). It’s also possible for different groups to produce different scores for the same official, depending on the group’s policy objectives.

Some pledges can oversimplify complex issues, while others may make small issues into major policy debates. That’s why it’s critical for voters to carefully judge the results of scorecards and the implications of pledges.

It’s also why pledges and scorecards are only pieces of the larger, robust information pie. They can be very helpful for voters who want to identify and support candidates who share their policy goals. But for other voters, more options for getting that robust picture of a candidate are necessary. Next week, I’ll discuss one of the oldest methods for providing robust information: the words of candidates themselves.

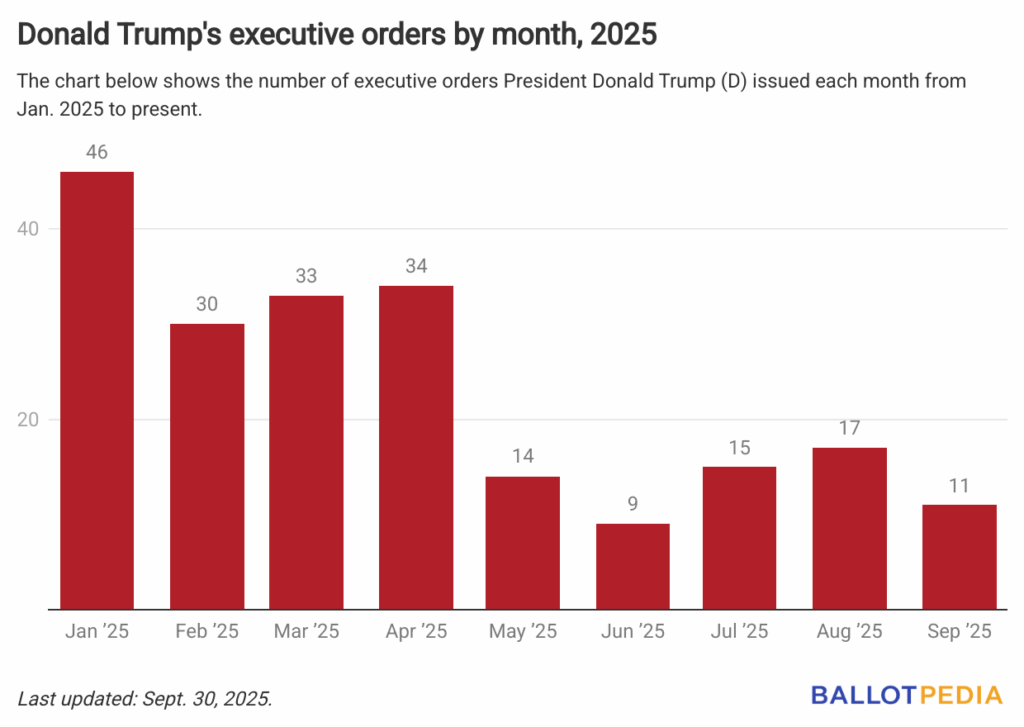

September marked President Donald Trump’s second-lowest month for executive orders in his second term

President Donald Trump (R) issued 11 executive orders in September, bringing his total to 209.

In June, Trump signed the fewest executive orders—nine—than in any other month in his second term. He issued 46 executive orders in January, the most of any month during his second term.

Through the end of September, Trump issued the 10th-most executive orders among all U.S. presidents, with 429 executive orders across his two terms in office.

Franklin D. Roosevelt (D) issued the most executive orders of all U.S. presidents, with 3,721 executive orders during his 12 years in office. William Henry Harrison (Whig) issued no executive orders during his one month in office. Three presidents issued only one executive order each: James Madison (Democratic-Republican), James Monroe (Democratic-Republican), and John Adams (Federalist).

Click here to view the titles and text of each executive order Trump issued in September.